One of the most significant issues with any idea is passing it on to others; how to teach, learn, and to whom.

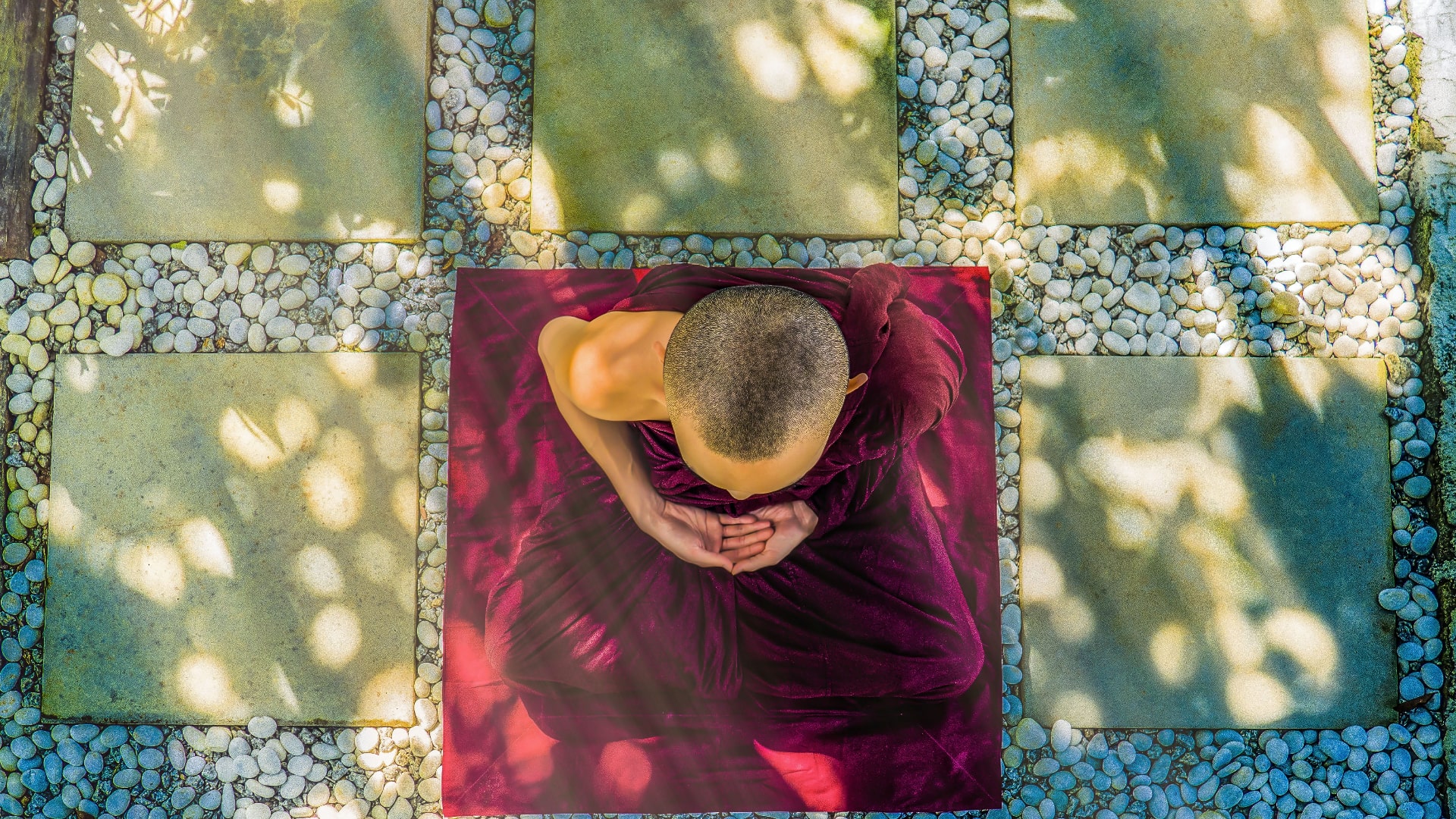

Buddhism recognises what it teaches is not easy to comprehend, so it’s developed many methods to get the message across. Different schools in Buddhism use their own methods.

The methods vary, the debates in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, Koans in Rinzai Zen, sitting down and paying attention in Soto Zen.

Therein lies what in Buddhism is called Upaya. It refers to guidance along the path of liberation. Upaya is often used with Kausalya(कौशल्य, “cleverness”), Upaya-Kausalya meaning ‘skill in means’, or ‘skilful means’. To teach requires skill, and such skills are often not evident.

Buddhism is complex because we’re trying to see beyond our illusions and limitations. But we can’t do that when locked within illusions we don’t understand or see. The solution, the path ahead, is staring us in the face, but to see that requires some clever methods.

Skilful means can be stories, reasoning and logic, koans, parables, and paradoxes.

Burning House

In the Lotus Sutra, there is the Parable of the Burning house. In brief, there are children inside a home that’s on fire, but they don’t know this. Their father is outside needs them to get out, so he shouts out that he has a special toy for each of them if they leave. However, he doesn’t have those toys, so he tells a lie of sorts.

The Buddha speaks to his disciple Shariputra,

“Shariputra, suppose that in a certain town in a certain country there was a very rich man…. His own house was big and rambling, but it had only one gate. A great many people—a hundred, two hundred, perhaps as many as five hundred—lived in the house. The halls and rooms were old and decaying, the walls crumbling, the pillars rotten at their base, and the beams and rafters crooked and aslant. At that time a fire suddenly broke out on all sides, spreading through the rooms of the house. The sons of the rich man, ten, twenty perhaps thirty, were inside the house. When the rich man saw the huge flames leaping up on every side, he was greatly alarmed and fearful and thought to himself, I can escape to safety through the flaming gate, but my sons are inside the burning house enjoying themselves and playing games, unaware, unknowing, without alarm or fear ….

….I must explain to them why I am fearful and alarmed. The house is already in flames and I must get them out quickly and not let them be burned up in the fire! Having thought in this way, he followed his plan and called to all his sons, saying, ‘You must come out at once!” But though the father was moved by pity and gave good words of instruction, the sons were absorbed in their games and unwilling to heed them. …

….I must now invent some expedient means that will make it possible for the children to escape harm. The father understood his sons and knew what various toys and curious objects each child customarily liked and what would delight them. And so he said to them, ‘The kind of playthings you like are rare and hard to find. If you do not take them when you can, you will surely regret it later. For example, things like these goat-carts, deer-carts and ox-carts. They are outside the gate now where you can play with them. So you must come out of this burning house at once. Then whatever ones you want, I will give them all to you!’ “At that time, when the sons heard their father telling them about these rare playthings, because such things were just what they had wanted, each felt emboldened in heart and, pushing and shoving one another, they all came wildly dashing out of the burning house.

Abridged Excerpt from the Lotus Sutra, translated by Burton Watson.

In one sense, the story is allegorical as it shows the burning house, the world of change and dissatisfaction, and outside is liberation and Nirvana.

But it shows that it’s sometimes necessary to tell white lies and half-truths to teach others to get them down the path of liberation.

How Buddhist get us to see the illusion that plagues us and the reality that lies beyond is what Upaya is for.

Gambits

“Art is a lie that makes us realize truth.”

Pablo Picasso

A particular technique, doesn’t have to be true in the strictest sense. It shows these methods are more expedient than truth; useful, but not based on facts. It’s there to bring the practitioner closer to a true realisation.

Upaya and the Buddhist way is about meeting people where they are at, to tailor teachings to suit the recipient.

It’s why stories can shape our attitudes and ideas towards the world.

Little white lies can be necessary for getting us to awaken. They are ‘sleight of hand’, a risky strategy that hopefully gets you to see the truth—a gambit.

The paradoxes of Koans are an example. By forcing you to confront an impossible puzzle, it makes us question how and why you’re trying to solve it. Koans use concepts and paradoxes to point out the limitations and absurdity of concepts.

We think we can solve the paradox using the mind, so we get to work. One day as I did, I discovered such riddles are impossible to solve, and insight follows – There is no secret ingredient.

Think of prose that deliberately breaks the rules of grammar. It makes no sense. A koan breaks the rules of reason, so it makes little sense. The insight lies in seeing that you do obey rules and expectations. For a Koan, it’s there to break you of the neediness for the answers that makes sense.

The aim of Buddhism is always the same: the transformation of consciousness and mindset to see through and transcend the hoax of illusions we carry.

The methods are to move us outside the boxes we typically live within, to break the black and white myopic vision we have of ourselves and the world – The map is not the territory.

I had to ask myself why I am so needy for the answers? Gradually I understood; my insecurity, and my neediness caused my suffering. A paradox illuminates not the answer but the desperation for answers. (You might say that no answer is still an answer, but that’s more on semantics).

The teachings are not truths to grasp, but they’re still lessons to learn. They are there to open our ignorant minds and let some insight in.

Closing thoughts

‘You can’t understand Buddhism by grasping for it, but neither can you understand it by not grasping for it.’

Trying to get people to wake up to reality involves some odd and clever ways; this is Upaya or skilful means. Letting go of bad ideas and falsehoods about how we work as people and how the cosmos works.

Buddhism is a means to an end, not an end of itself. Its teaching methods help us find enlightenment; but the ideas themselves are not enlightenment.

To ask ‘Is Buddhism true?’ is a meaningless question and demonstrates you don’t understand it. It’s a mistake to think there is a set of principles to grasp in Buddhism. Buddhism is empty of self like all the other things in the universe.

‘Emptiness in Buddhism cleanses the mind like a fine sorbet cleanses the palette.’

It’s not about grasping for answers as letting go of the need for them. To wake up to a reality beyond conceptual thought.

‘Buddhism is a vehicle for a good life, not an ideology to cling to.’