‘Insofar as the senses show becoming, passing away, and change, they do not lie. But Heraclitus will remain eternally right with his assertion that being is an empty fiction. The “apparent” world is the only one: the “true” world is merely added by a lie’.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

Sunyata, or Emptiness, is one of the ideas put forward by the 3rd-century Buddhist Mink, Nagarjuna; it’s considered one of the most critical Buddhist ideas and shaped the Mahayana lineage of Buddhist thought.

The basic message of Emptiness is that all of existence and the objects or things are empty of intrinsic nature or enduring existence.

It’s an idea that goes back to the Buddha, his lesson of Non-Self, Anatman/Anatta. What you think of yourself, which we label as self or ‘I’, ‘Me’ is an illusion, a narrative of ideas and beliefs. All phenomena, including your existence, dependently arise and are caused by or based on other phenomena.

Misunderstanding

Some have thought this notion of empty existence suggests a Nihilism, that nothing exists. But this is a misunderstanding that Nagarjuna explicitly refutes and points to a misunderstanding of his ideas.

Another mistake is thinking Sunyata is some basis of existence or reality, a bedrock. Nagarjuna also rejects this; Sunyata is not some primordial reality that’s the basis of this one. It’s a claim that doubts the belief there is a bedrock and any ideas to claim it.

Two Truths

I see bodhisattvas

Lotus Sutra (Kubo and Yuyama translation)

Who have perceived the essential character

Of all dharmas to be without duality,

Just like empty space.

I first started to understand Emptiness through the Ship of Theseus thought experiment, also known as the Sorites Paradox or the Fallacy of the Heap.

Consider any object or thing; if you keep replacing its parts, at what point does it no longer remain as that same thing? Say, for example, a car; if all the parts are replaced, there’s nothing left of the original, is it the same car?

There is no part where we can say this is the essence of the car. A noteworthy point is the parts are made up of smaller parts. You can keep drilling down into smaller and smaller pieces, but you’ll never find a part that doesn’t change. It applies to all things even our very thoughts, experiences and ideas.

This is the Two Truth Doctrine of Nagarjuna. There are activities going on here, the changing interconnected reality, and the ideas we use to discuss it.

Language of the Void

‘The language is hard to grasp because it’s pointing to is not graspable.’

The idea of Anatman and Sunyata is challenging because it goes against our typical mental activity. Western philosophical thought is based upon essences; the Atomos (Greek: uncuttable or undivided). There is the personal Atomos, a Soul, Self the essence of existence.

It’s hard to understand because it uses the language of absence, a statement that explains what’s not there, void, a lack of existence. When we seek to live by grasping for an answer, for understanding, what exists, what’s true. But Sunyata is saying there are no answers.

Working with the notion of absence seems odd, but we talk about it in many areas.

We denote absence with words like—Asymptomatic, Amoral, Atheism and Anatman. It’s like the hole in a doughnut. ‘The doughnut has a hole’, but how can a doughnut have something that’s not there? Instead is the absence of a doughnut. The Japanese term Mu, has many meanings but also denotes an absence. (The Chinese use Wu). Mujō (無常) means ‘impermanence’. Mushin means ‘No mind’.

Sunyata is like the Free From section of your supermarket; it's free of gluten, dairy, peanuts, and everything, including a self or essence. It's the ultimate non-allergenic existence.

The point of this negative, privation language is to undercut our reflex activity of clinging, which leads to suffering.

The Art of Emptiness

Reality can’t be grasped, only experienced.

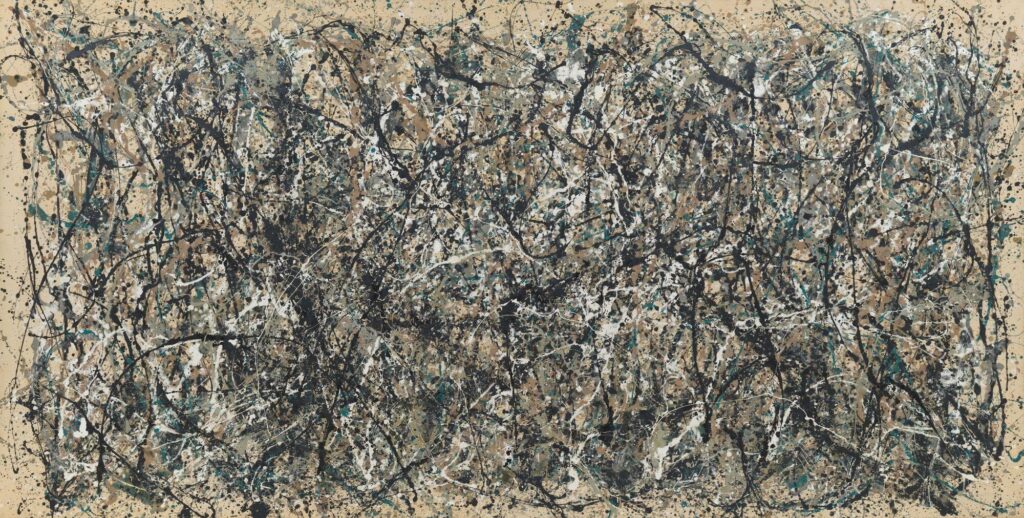

Consider a Jackson Pollock drip painting. There is something there, but the image depicts nothing discernible. No pattern or form we recognise, no message to grasp and understand. In the something (painting) there’s is nothing (no emptiness). The painting is therefore empty, of essence.

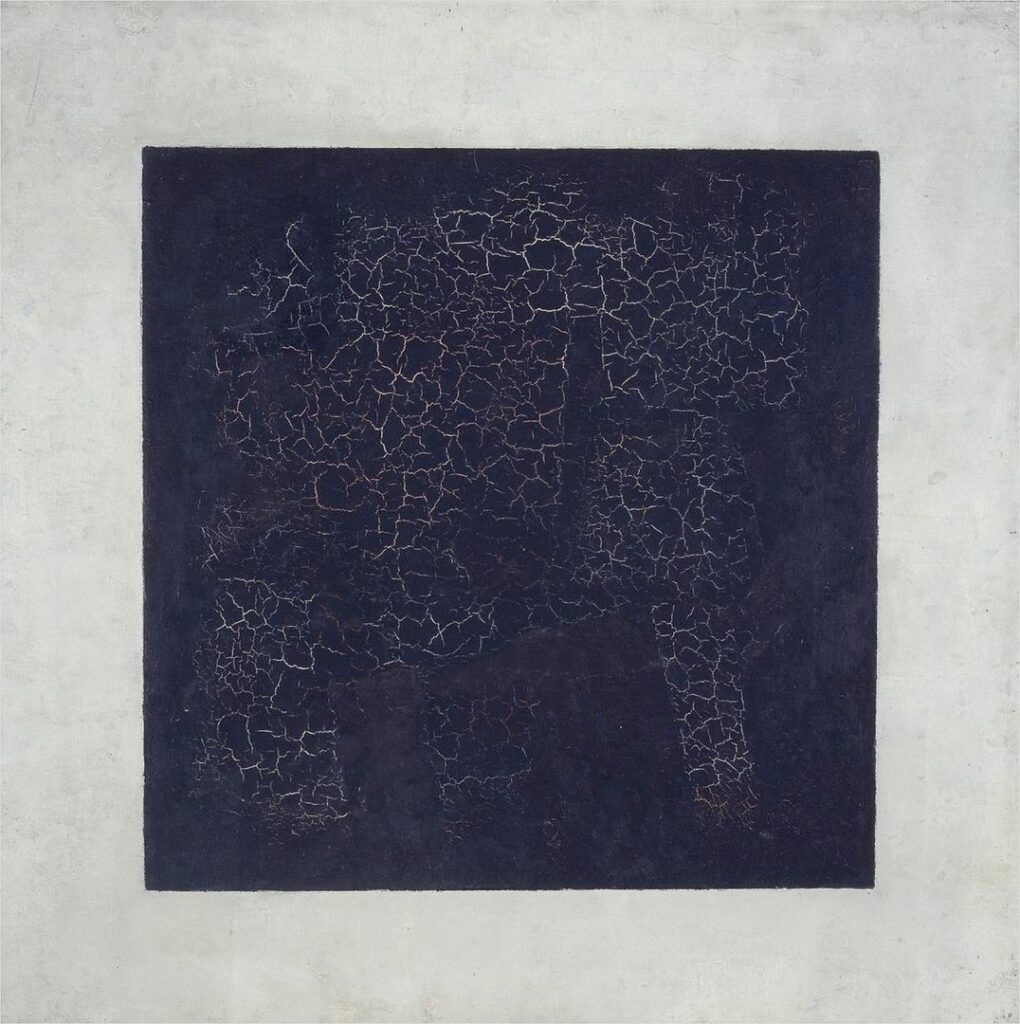

Instead of emptiness as chaos, think of it as the emptiness of absence, like Black Square by Kazimir Malevich or a Mark Rothko field painting. Same again there’s no depiction, no form, no object to assess, and understand.

Sunyata is often compared to void, space, the sky, a complete openness, or ‘unobstructedness’, a boundlessness. This emptiness is the true nature of reality.

Non-Self and Sunyata are messages; there’s nothing to grasp. Such an awakening tells us to cease grasping for an answer, for certainty, because that’s where suffering arises.

Closing

In Buddhism Non-Self or Emptiness (Śūnyatā) is the key, the path liberation from suffering.

All things, phenomena, and objects are empty of a fixed, enduring self-nature. Sunyata says there is no essence, defining feature, or elements that make things what they are. Existence is an interconnected process of change.

To reduce suffering is to recognise there’s nothing to attain, to grasp; instead. Sunyata reminds us life will always be a mystery. To grasp for a concrete understanding of life is to walk on the path of suffering. To let go of knowing how it all works and why we are here is to be liberated from suffering.

For more on Buddhist ideas sign up to my newsletter.

Bonjour,

Si le bouddhisme conçoit la conscience (entre autres) comme ”vide”, comment cette même conscience (vide) peut – elle concevoir sa vacuité ou la vacuité des phénomènes?

‘If Buddhism conceives of consciousness (among other things) as “empty”, how can this same consciousness (emptiness) conceive of its emptiness or the emptiness of phenomena?’

Thanks for your comment Jean-Pierre.

The way the Buddhists see consciousness to understand it’s like all other phenomena.

All things, including consciousness, are based upon other causes and conditions. My consciousness can conceive of it by seeing this web of relationships and accepting that our minds are no exception. For example and ecosystem or our the anatomy and physiology of or bodies.

The key insight is to remember all things are based upon multiple causal factors or Interdependent co-arising.

Hi there,

Really enjoying your articles but am struggling with your spelling and grammar! It is all over the place! Do you need a proofreader to go over things before you publish? I am happy to read through before you post – the spelling and punctuation really detracts from the flow of your content.

Regards

Hi Danya, thanks for the feedback and the sub. I do use Grammarly when I write so the spelling and grammar should be sorted well enough. Maybe it’s the subject I’m writing about. Buddhist ideas are not easy to follow, and I wonder how well my thoughts on the subject come across.

Regards

Hi again Richard,

I just found this article way deep in my inbox so had a re-read. I am a pedantic proofreader and can spot small comprehension errors a mile off so pay no attention..the few mistakes here have not interfered with the subject matter at all and your thoughts have come across fine :). I have recently completed a course on Emptiness and found it really difficult to ‘comprehend’…I really like how you have used some metaphors here because it makes starting to understand the concept a little easier. We have small minds don’t we! Working hard at expanding mine but of course one really needs to start at the beginning with Mindfulness practices and Shamatha (Calm Abiding) meditation before moving onto deeper insights.. Are you a practicing Buddhist?