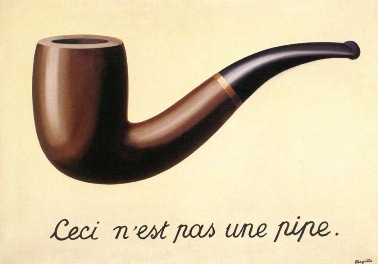

The painting below says ‘This is Not a Pipe?‘ but that makes no sense, because clearly it is a pipe. But the topic here is art and philosophy, so we need to look deeper to understand the meaning.

The claim ‘This is not a pipe’ is correct. It’s not a pipe, it’s a representation of a pipe. (Or a representation of a representation, because it’s on your screen). It’s a painting by René Magritte, The Treachery of Images and it points to a three-way paradox about the objects and things we talk about and their existence.

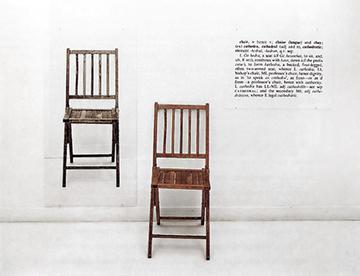

It’s a type of art Magritte and others used to question and overthrow the excessive rationalism of society. Another example is the One and Three Chairs exhibit by the artist Joseph Kosuth. The exhibit had a real chair, a photo of a chair and a dictionary definition of a chair. The Three chairs, they’re the same yet different? Two are ideas, the third the real chair.

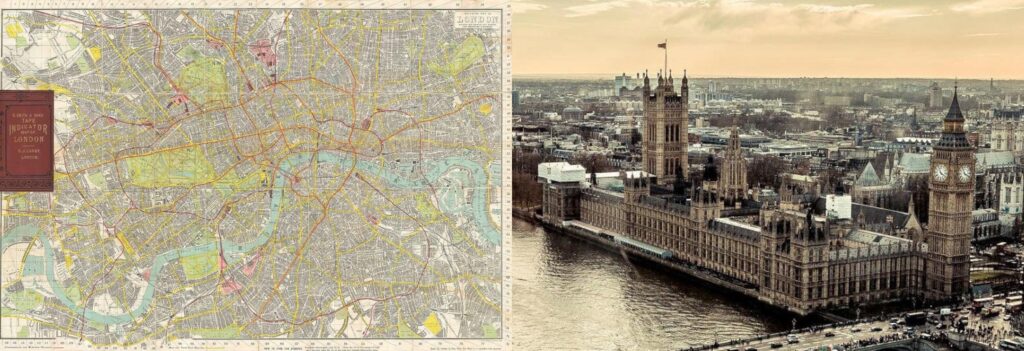

The Map vs Territory

‘We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies.’

Picasso

What’s going on here are two different but related points or realities, a duality between what’s real or observed and our ideas about it. The Map is about Territory. Just as a map of London versus London itself.

An important point to make here is if you destroy the map the territory remains just as if you destroy the altimeter of a plane, the plane doesn’t fall out of the sky. Again It shows they are related but not the same.

It was a Polish-American Alfred Korzybski who popularised the term that fits here; ‘the map is not the territory’. Language, imagery, art, maps, models, schematics etc are ideas about reality not reality itself; they depict a simple idea that refers to a real object or reality. We have to abstract a complex changing reality, make it simpler so we can talk about it. It shows we can never grasp reality with language or ideas because they will always be poor imitations of the real thing.

Stereotypes are a practical example. We carry with us assumptions about ethnic groups groups, companies, and organizations. You might call them prejudices, but people don’t always fit those assumptions. The problem arises when we deal with our prejudices about a person rather than the individual. The ideas have become more important than the facts of reality, more on this below.

Another example is a grayscale. The reality is a scale with no distinct boundaries, but that’s not useful, so artists like myself will simplify and use an artificial scale of four, five or even greys to paint with.

What is meant by ‘Map’

‘I don’t know where the artificial stops and the real starts’

Andy Warhol

Humans use countless types of “maps” to represent and make sense of reality. These include literal maps and schematics, but also paradigms and scientific theories that shape our overarching worldviews. Stories, narratives, and metaphors in language reflect how we conceptualize existence. Visual arts like paintings and sculptures depict ideas rather than precise reality. New technologies enable increasingly complex simulations and virtual realities that model aspects of the world.

All of these maps are human abstractions – models, theories, hypotheses that we construct to understand and explain the universe around us. However, we often forget that our maps are inventions that describe reality, not reality itself. The maps are not the actual territory. We must be careful not to mistake our theories and models for facts before we have sufficient data to support them. Our representations of reality can easily become confused with reality itself.

Ultimately, the human mind requires these invented maps and narratives to perceive, navigate, and make sense of the cosmos we inhabit. But we must remember they are our own abstract creations, not the literal truth.

Pipes, chairs, and maps may seem like obscure art or philosophical talking point. But they show a depressingly familiar truth: Our ideas and beliefs are not as certain as we like to think, and we should not be so confident in our appraisal of the world or ourselves.

This duality between a Map and its Territory, or reality is related to Buddhist notion called the Two Truths, and a big problem is we have a tendency to fixate on the Map, not on the reality it points towards, making our ideas more important than the reality we face.

We often try to twist reality to fit inside a theory, model, or map. I explain more in my other post on hypostatisation or reification fallacy. But Ideas can become more important than the reality or world we face so we cling to ideas despite evidence that they are wrong or misleading. We think we have a good handle on reality, not realising how delusional we are.

There are two realities: the perceived and the fabricated, the territory and the map. Our error is believing reality is as simple as our maps and ideas. Further more we can place far too much value of maps at the expense of a reality that is staring us in the face the we start to twist reality to fit our idea.

But here’s a truth. ‘What is reality cannot be washed away, and what is washed away can never be reality’. That is to say, we can destroy all the maps, model and ideas, and reality still remains, which can never be destroyed.

Reality and its truth get buried or forgotten under layers of falsehood and half-truths because we’re fixated on the map, not the territory. We are all prone to this attitude, so we must be far more careful about claiming certainties and more open to changing our minds when new information arises, especially where it challenges our preconceptions.

Here also can be found the teachings of the Buddha, who taught that addressing the illusion and delusion of the mind is a big part of liberation.