If I see one mistake cropping up repeatedly in social discourse and our personal lives its the belief that the world must fit our beliefs and expectations.

What do I mean by this? Consider an everyday scenario: Caught in a traffic jam. Our attitude is, ‘It should not be happening like this!’ Our expectations are not met by the reality we face. So we get upset and look for someone to blame.

But what’s going on here? We all have ideas, expectations about how the world works or feel it should work. These are beliefs, ideas or values we hold to be important. They can be from small to great, from private opinions, like stereotypes to whole religions with ideas about life and the cosmos.

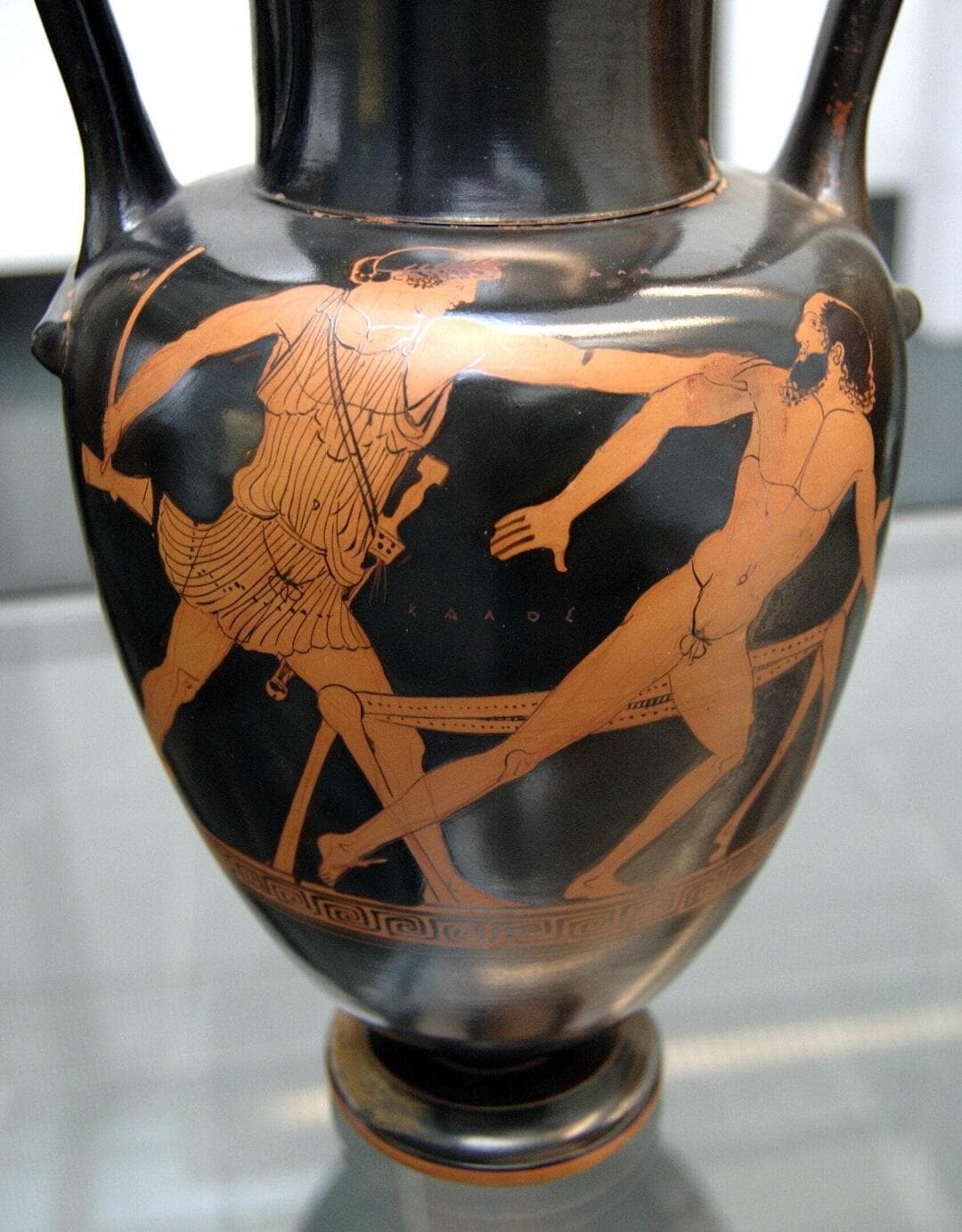

In Greek mythology, there’s an innkeeper, Procrustes. His inn contains an iron bed (or perhaps two in some accounts). If a guest is too short, he will stretch them on the bed. If they’re too tall, he would cut off their legs. Everyone who came to stay at his in fitted the bed perfectly. It’s a metaphor about our relationship towards our ideas, or maps.

Yet we forget there’s a difference between reality and our ideas. The map is not the territory; there’s a difference between theory and practice, of reality and our models and maps about reality. But we seemingly fail to see this distinction.

‘Within every conception, lies a misconception, that being the idea is the reality.’

Richard Collison

Problems arise because of our illogical and emotional attachment to our maps and the belief they are true depictions of the world.

In a situation where our theories or maps don’t match the reality. Instead of altering our theories to fit the facts, we twist the facts to fit the theory. The fiction of our thoughts, ideas and beliefs becomes more important than the facts of reality. As Sherlock Holmes says in A Scandal in Bohemia, “I have no data yet. It is a capital mistake to theorise before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories instead of theories to suit facts.

Our mind tries to squeeze or simplify an unruly and mysterious existence into something more manageable: simple ideas, beliefs and assumptions. This twisting, stretching of reality to fit the map is called the Fallacy of Reification, also known as Concretism, and Hypostatization. Think of it as trying to stuff clothes into a box, or suitcase. The case is our beliefs and we try to fit reality inside them.

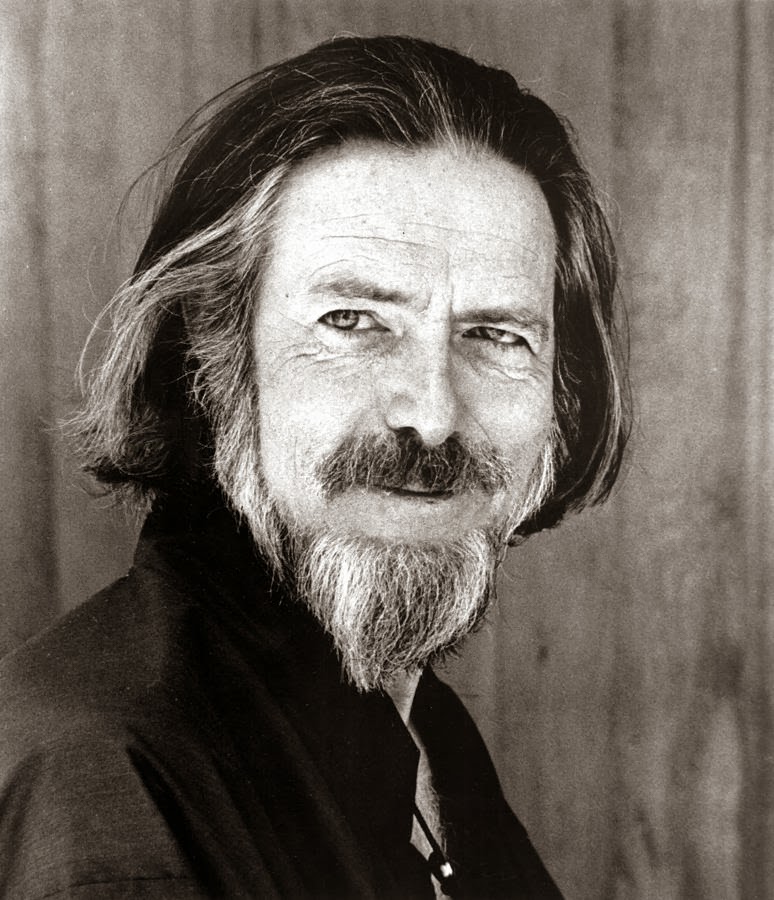

‘If you take words too seriously, you are like someone that climbs a signpost instead of going where it points.’

Alan Watts

Another name for it comes from the Mathematician and Philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, “There is an error, but it is merely the accidental error of mistaking the abstract for the concrete. It is an example of what might be called the ‘Fallacy of Misplaced Concreteness.’ It’s where abstract or hypothetical ideas are treated as concrete, even physical reality.

Take, another example, when we lose our car keys. We look where they should be and find they’re not there (reality does not match expectations). Then we look in some other places, then bizarrely, we go back and look again as if the keys would magically appear! However, our expectations still need to be met; we must find our car keys. So we get angry and flustered because we’re going to be late. In this scenario, our attitude is that reality is wrong because we have to be in the right; our expectations for a smooth, simple life must be met because the world owes us.

Scenarios are not always so innocuous; sometimes, in the most extreme, they involve the risk of death. Imagine finding yourself lost in an unfamiliar jungle after an air crash. Or stranded on a remote island or lost at sea in a lifeboat. Here, the reality doesn’t fit our expectations in a big way but it’s the same issue, are we clinging our expectations or adapting to the situation?

We can become so attached to our narratives that we fail to see it’s just a story. It shows that how we relate to our creations like ideas is significant. Our maps and models become so sacred that we fall in love with them, like Pygmalion, who fell in love with a statue of a woman he created.

This is the danger of religion and worldviews in particular, the idolatry of ideas. We hold onto them long after their usefulness has faded. Such naïve trust in our ideas can get us into a lot of trouble and cause a lot of suffering. It’s like we’re bashing square pegs into round holes, we blame the world or others instead of blaming the idiot holding the hammer.

Back to Reality

‘When a wise man points at the moon the imbecile examines the finger.’

Confucius

To move beyond this clinging attachment in ideas is a matter of self-awareness and taking our insecure ego out of the equation. We need to recognise our maps are not the territory and accept reality for what it is. Our theories should be adjusted to fit the facts. Our ideas are not not unassailable truths about the cosmos but useful tools. We must try to notice when our egos jump in with the desperate need to be in the right, even if that means ignoring good evidence and advice to the contrary.

We need to do better at critically examine our beliefs and assumptions, to realise where and when we’re twisting, reifying reality because we can’t accept it.

The world doesn’t have to match our expectations, our maps are not the territory

Our tendency to twist reality to fit our needy desires is derailing so much social dialogue and debate. As such, it sabotages our efforts to solve the myriad of problems we face.

In the Suraṅgama Sūtra, a significant Chinese work on Buddhism is says:

Consider this example: suppose someone is pointing to the moon to show it to another person. That other person, guided by the pointing finger, should now look at the moon. But if he looks instead at the finger, taking it to be the moon, not only does he fail to see the moon, but he is mistaken, too, about the finger. He has confused the finger, with which someone is pointing to the moon, with the moon, which is being pointed to

(Hsüan Hua and Buddhist Text Translation Society, eds., The Śuraṅgama Sutra: A New Translation (Ukiah, Calif: Buddhist Text Translation Society, 2009), “Visual Awareness Is Not Dependent upon Conditions).

We developed rationality to understand the world, the world doesn’t develop to fit inside our rationality.